Quicklinks

Definitions

- None at the moment; suggest some!

Introduction:

Formwork is the system/structure of boards, ties, and bracing used to create a ‘form’ (or ‘mold) which wet concrete is poured into. After the concrete has cured, the formwork is removed and it leaves the resultant concrete form.

Materials

Formwork for concrete can be made out of a number of materials, but the most standard is ¾” plywood. Typically the plywood side facing the wet concrete is coated in a material impermeable to the wet concrete; such as oil, water-resistant glue, steel, or a hard plastic.

- The material and coating (if provided) on the formwork, drastically increases the ability for the formwork to be reused as well as last for multiple uses. In a more sustainable construction process, and especially on projects such as towers where the floors are repeated, the formwork will get reused multiple times in their lifespan.

- Prefabricated steels forms are common on high rise projects and used for their strength and durability.

Strength & Constructability

The main requirement is that the formwork structure needs to be strong enough to withstand the immense outward pressure the wet concrete creates. A secondary aspect is constructability, and that the formwork needs to be relatively easy to construct and easy to remove.

- In certain applications like lot line conditions, the formwork may never be removed and is instead abandoned in the space.

Tolerance

You can get tight tolerances with a great subcontractor, but concrete is a messy business and difficult trade to master. Forms can shift, weight can affect plumbness, and so on. The tighter the tolerances required, also will translate into more money as extra time is needed to re-verify heights, take surveys, etc. Therefore, dimensions and elevations should ideally be struck in ½” increments.

Aesthetics & Finish

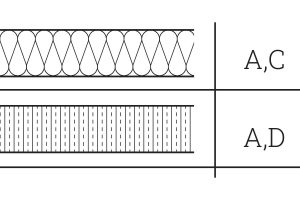

Patterns & Formliners

Because the wet concrete touches the formwork, you can translate a pattern into the finished concrete from the formwork, whether for aesthetic or other reasons.

- A common example of this is board formed concrete which uses dimensional lumber as the formwork, which translates the wood grain texture.

Formliners are another way of creating a pattern across a surface. These liners are typically made of a plastic or plastic-like material that is elastic and can be easily removed and then reused on another piece of the project. The patterns have repetition so it can seamlessly get used across the project.

- Fake stone walls, and geometric patterns are common

Exposed Ties

On in-situ surfaces that will be left exposed, if there are ties as part of the formwork, some thought needs to be given to where those ties are located and the spacing. This is not only an aesthetic concern, but needs to be coordinated with the structural requirements of the formwork.

- Tadao Ando is one of the best at this

- Sometimes these ties are either exaggerated or hidden with reveals, see below for more information.

Reveals

Reveals are commonly referred to as rustication strips. These are typically pieces of a material secured to the formwork which once removed, leave a deep reveal in the finished concrete.

- Commonly done with wood due to its easy workability, but also neoprene (rubber) or a hard plastic can also be used effectively

- Many times a bevel needs to be introduced on one or both sides to allow easy removal of the strip from the formwork.

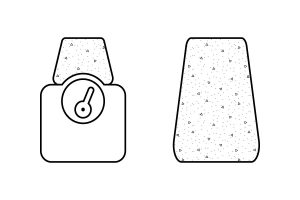

Form Ties

Form ties are typically metal wires or rods that are placed at regular intervals across the formwork to hold opposite sides together. The concrete exerts an immense pressure outward, which puts the ties in tension. The ties excel in this structural instance and therefore thin ties across the form will hold the gap and prevent the outward collapse due to the weight.

- When the concrete has finished curing, the forms are removed and the form ties are abandoned in the concrete. The ends can be cut off and polish relatively clean.

- Some ties are threaded and they allow reuse for the next location (by unscrewing from their pour location)

Tie Holes

Cone shaped pieces are placed at each end of the tie flush with the concrete form. When the concrete is cured and forms removed, the cone/cylindrical shape is left. This allows the tie to be cut lower than the face surface of the concrete. The holes are either left as-is, plugged with rubber pieces, or patched with grout or sealant.

Special Forms

There are many special types of form construction materials and techniques that have been developed over the years. These are mainly to either decrease construction time, or look to be better insulating using technological advancements in materials.

Slip Forming

Slip forms move while the concrete cures. This is compared to letting the concrete completely cure. Slip forming is extremely common for repetitive structures, such as tunnels and high-rise building cores.

- The entire form is created with a working platform and structural supports which allow for a jacking assembly. The form moves upward at about 6” to 12” per hour while concrete is being poured – depending on concrete type and application. The form is typically paused while pours are not being completed such as nights and weekends.

- The way slip forming works is that by the time the formwork exposes concrete, the form is tall enough where the concrete has cured. If you need a longer cure time, you can simply increase form height or decrease form movement.

Flying Forms

Flying forms consist of large fabricated sections of framework that are removed once the concrete has cured and reused to form an identical section above. They are often used in buildings that have highly repetitive elements such as high rise buildings and especially cores.

- This allows repetitive floor plates to be quickly created and drastically reduces construction time for these similar elements.

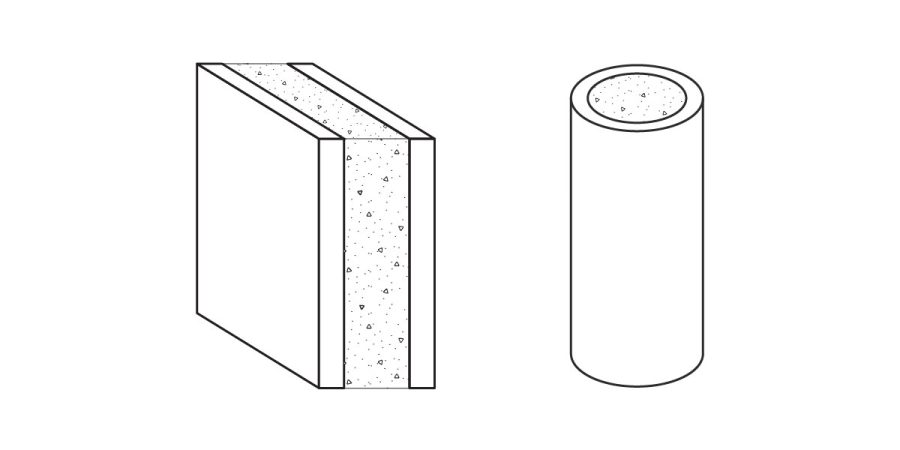

Insulated Concrete Forms (ICF)

ICFs are standardized polystyrene forms that provide the formwork for concrete. ICFs are unique because they are designed to be left in place after the concrete cures. The polystyrene material provides excellent thermal performance, and finish materials can be applied directly to the plastic or ties which are integrated into the formwork design.

- ICFs speed up construction and provide insulation in one process. The blocks are designed to be an interlocking system, and therefore can be placed by unskilled workers with relative ease.

- When used above grade for exterior walls, they provide great sound attenuation and less air infiltration

- Formwork can incorporate reinforcement through rebar, and some tie systems provide guides to hold the rebar off the walls for coverage.

In Practice

Most often used for single family houses and small commercial projects.

- Depending on the height of the wall, ICFs can reduce the amount of bracing needed.

- Concrete is typically placed in lifts (layers) to prevent blowout of the form.

Code Requirements

Code generally requires both sides be protected from fire as well as sun and weather exposure.

- This means a finish layer, layers of waterproofing, or cladding material of some kind needs to be provided. This will vary depending on the design, local code, and existing site conditions.

Openings

Openings are able to be provided in ICFs. The formwork space needs to be sealed properly and the opening supported until the concrete is cured.

3 Main Types of ICFs

- Block: Most common type that is what people think of when you say ‘ICF’. These can vary from the side of a concrete block to several feet long. The blocks have interlocking edges and integrated ties to keep the two sides of the block together. When placing blocks, they should be stacked similar to bricks and offset the bonding seams.

- Panel: Larger flat pieces typically up to 4’ x 12’. These are basically a block form but much larger with ties already placed throughout. These go up quicker but allow less ins and outs in the wall footprint.

- Plank: Flat forms up to 12” high and 4’ to 8’ long. Essentially block forms but much elongated. Similar to panels, will go up quicker but allow less ins and outs.

Economy

The process of pouring concrete can be quite expensive. Besides the raw materials that go into concrete and rebar, the next biggest controllable expense is the formwork. An architect can help reduce the cost of the formwork specifically by following a couple of guidelines:

- Forms should be designed to be as reusable as possible. This means there should be uniformity in the beam and column sizes, openings, and standardization in all other repeated elements throughout the building.

- Slab thickness and walls should be kept consistent, without offsets if possible. Structural requirements will force variations in the formwork and design, however, it is often less expensive to use a little more concrete to maintain a uniform dimension than to make adjustments or modifications. This is additionally easier to coordinate between consultants, and the uniformity in the field will decrease the chances of an on site error.

Tolerances

Because of the nature of concrete, tolerances are to be expected and needed in the concrete work. Its advisable to always design tolerance into your details to allow slight variations in the construction.

Rules of Thumb

- Typically in walls, columns, piers, etc. The maximum variation is expected to be ¼” per 10’-0”. The same is to be expected for horizontal elements like beams.

- Maximum variation for total height of the structure is 1” for interior columns and ½” for corner columns for buildings up to 100’-0” tall.

F-Number System:

An electronic instrument is used to take multiple readings over 12-inch intervals and develop a statistical evaluation of the flatness of the the floor. This is reflected in a single number ranging from 10 to 150.

- ¼” is about equivalent to 25

- ⅛” is about equivalent to 50

- As F-numbers increase, the flatness of the slab improves.

- F-Numbers are only used for slabs on grade.